Hymnbook Cantus Catholici

Its creation and content

ca. 8 min

‘Considering this pleasure (the pleasure of singing) relative and inherent to our Souls, so to not let the Devils, introducing salacious, obscene singing subvert everything, caused God Psalms and Hymns, so that from those things could arrive together pastime and benefit.‘ -commentary on Psalm 14 by John Chrysostom, in the introduction

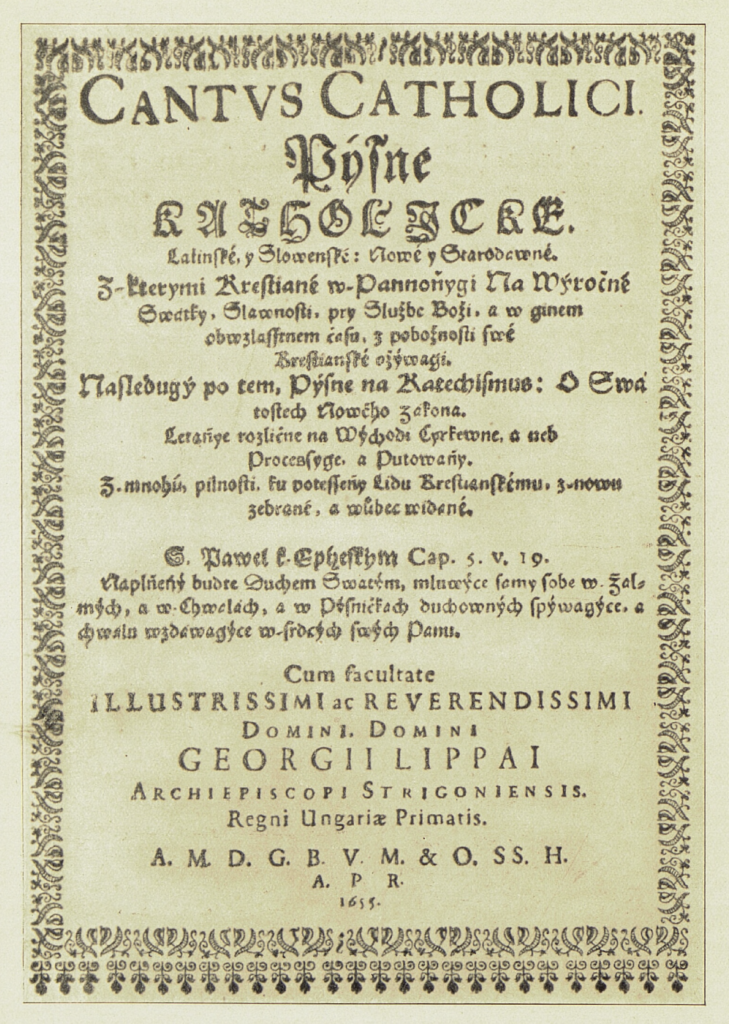

Hymnbook Cantus Catholici (1655) is the first printed catholic hymnbook issued in Slovak. Circumstances of its release indicate general and musical realities and issues of the era in which it has been compiled. The hymnbook preserved historical phenomena, acted as a medium in passing material down or popularised many melodies and texts. It has greatly partaken in cultivating a congregational singing practice and influenced future evolution within the Slovak church music scene.

In the second half of the 16th century, the Roman Catholic church in the Kingdom of Hungary found itself in a critical situation. With the influence of protestant reform movements, it became a minority religion. Thanks to multiple canonical visitations completed between 1526 and 1561 we can discern that many priests were proponents of the Lutheran movement, most probably as a result of pressure from the landowning nobility. Religious superiors frequently mention changes or cuts to a typical Roman mass offered by these priests. The overall image that the visitations by the Archdiocese of Esztergom offer illustrate fragmentation and discord in the organisation of spiritual life in the kingdom. A similar or far greatly developed situation has been a reality in many European countries, resulting in calls for reform inside the Roman Catholic church itself.

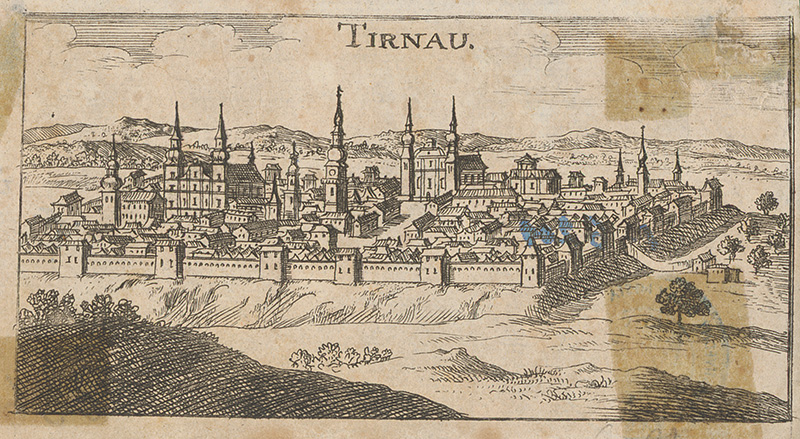

Council of Trent (1545-1563), alongside launching counter-reformation to tackle the loss of believers, addressed issues related to sacred music and mass celebration. The council raised particular concern over the clarity of text set in embellished polyphony. Counter-reformation in the Kingdom of Hungary was staged in the city of Trnava, where a diocesan synod of 1629 committed to carefully compiling hymns and chants used at liturgy into one hymnbook and to ‘cleansed of heretical’ content any disputable text. This task has been entrusted to Benedikt Sőlőši (1609-1656), a Jesuit monk and missionary.

Consequent Synod held in Trnava in 1638 decided, probably after the printed issue of the protestant ‘Cithara Sanctorum’ hymnbook in 1636, that the catholic hymnbook should be disseminated by print as well. Historians often describe Cantus Catholici hymnbook as ‘counter-reformative’ or ‘re-catholicising,’ underlining the rivalry of confessions. On the other hand, Sőlőši adopted or appropriated many texts and tunes from Cithara Sanctorum, which demonstrates to the mutual interconnectedness of these two worlds and to the popularity of protestant church music.

The hymnbook has been compiled during Sőlőši’s stay at Szendrő (today in Hungary), Košice, Kláštor pod Znievom and Spišská Kapitula (today in Slovakia). Slovak-Latin edition has been issued after a Hungarian-Latin edition (1651), however, both hymnbooks are independent in relation to their content. Both have been issued in the northern town of Levoča, with a later reedition of the Slovak-Latin cantional (another term for hymnbook) released in 1700 in Trnava.

The original issue of 1655 contains 336 pages and 296 hymns, of which 67 are in Latin, 228 in pre-codified, so-called Cultured Slovak (labelled ‘slavonicè’ in the hymnbook) and one hymn is Latin-Slovak. As the long title of the hymnbook states, it includes hymns old and new (respecting both reform and tradition), hymns for annual celebrations (categorisation according to the liturgical calendar- Christmas, Lent etc.), hymns for Feasts, different services (mass, vespers), occasional hymns (mainly for domestic use by the faithful) or hymns for catechesis (education). With its complexity, the hymnbook comprehensively statutes day-to-day catholic musical expression.

Three-pages long foreword emphasizes continuity in the tradition of saints Cyril and Methodius and their effort to mediate liturgy in the language of the common faithful, which is addressed as the nation of the ‘Pannonians’ in the foreword.

Sőlőši approached the hymnbook compilation in a role of an editor. He collected and recomposed musical material and translated and actualised texts to be considered fit in relation to reformed catholic rhetoric. The provenance of adopted hymns attests to the multiculturality and multiethnicity of the northern part of the kingdom and its ties to neighbouring Central European church music traditions, notably Czech.

Hymn Texts

Term ‘Ancient Hymns’ labels old Latin church chants (e.g. Victimae Paschali Laudes, Ave Maris Stella), which have been passed down in the Kingdom of Hungary since the middle ages, but also other chants, which have been popular among German and Czech Catholics. These were paradoxically archaizing as well as innovative. In a bid to form a closer relationship with the ordinary believers, after the Council of Trent, the church allowed the mandatory parts of mass (so-called ordinary- Kyrie, Gloria, Credo) to be sung in national languages, under the condition of priest singing or reciting them in Latin. That is why Cantus Catholici includes many of these ancient hymns in both their Latin and Slovak versions.

Moreover, hymns of Czech Utraquists (early Hussites) and Brethren are also specified as ancient. These were becoming increasingly popular in Slovak-speaking parishes in the first third of the 16th century. Amongst them are hymns, which remained integral to many hymnbooks of various denominations to this day- for example, the first Czech lent time hymn Kristus príklad pokory (Christ, example of humility) (1501) or Eastertime canticle Bůh všemohúci (God almighty) (1420). Protestant churches in Czech lands and in the north of the Hungarian Kingdom were united in their use of the Biblical Czech language, which is nowadays still used by many protestant communities in Slovakia.

Czech catholic hymnbooks are a major part of younger sources accessed by Sőlőši. The vast majority of texts and melodies were borrowed from Moravian hymnbooks- Cantus Catholici shares 129 hymn titles with the hymnbook of Jiřík Hlohovský (1622) and 91 with the hymnbook of Jan Rozenplut (1601). Original Slovak texts or translations, e.g. carol Čas radosti, veselosti (Time of joy and cheer) or New Year’s Vesel se lidské stvorení (Rejoice, mankind) and translations of Latin, Hungarian, Polish and Croatian texts form a wide and genre-varied group. In spite of these texts not being found in earlier cantionals, it is hard to discern that their author may have been Sőlőši, who also appropriated material from oral tradition.

Musical Setting

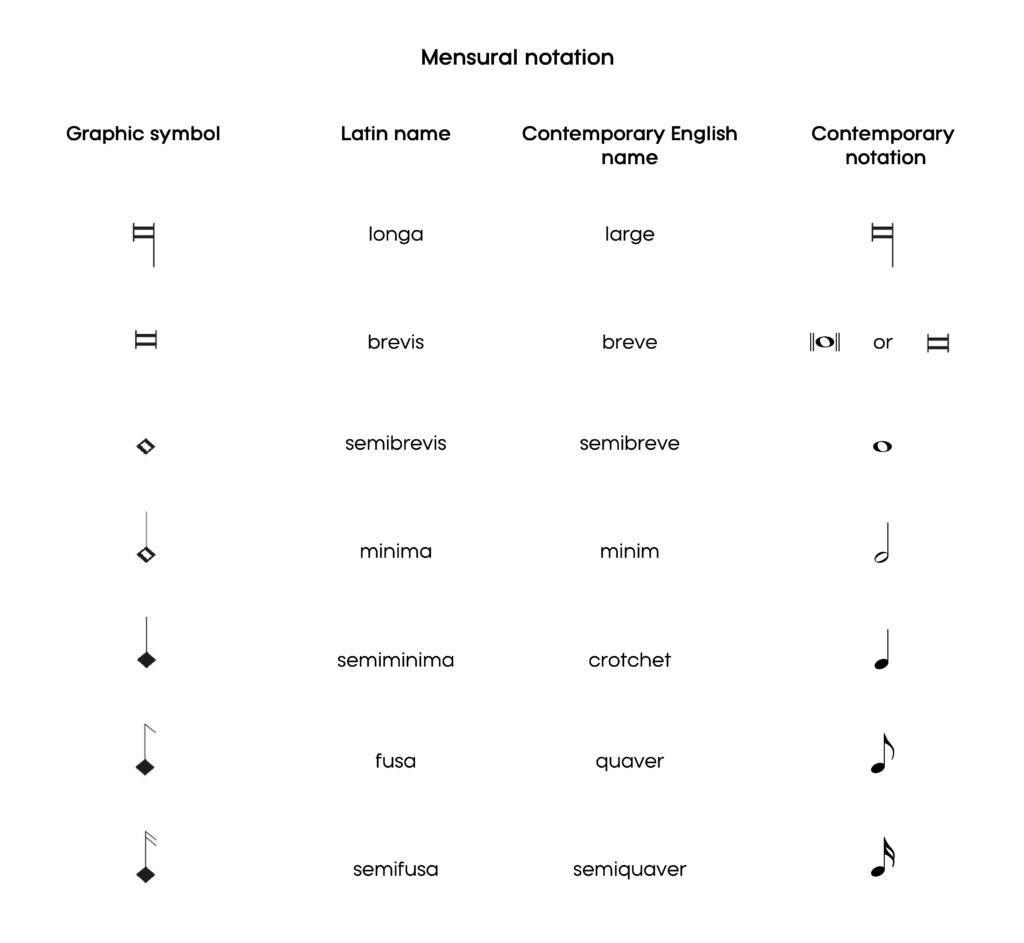

Texts are accompanied by music written in mensural notation, a predecessor of modern notation. Its main difference and advantage from preceding notation systems is the introduction of rules in measuring the lengths of individual notes. With the evolution of polyphony came the need for keeping individual voices together, synchronizing the singers. Even though Cantus Catholici only includes monophonic music, mensural notation was a widespread standard at the time of its issue and easily usable in print.

Melodies and tunes in the hymnbook are influenced by more than a century-long central European cantional tradition, in which tunes of Gregorian chant, pre-protestant cantia, humanist metrical odes, psalms of French psalters and newer versions of reformed and catholic spirituals were preserved. Material collected by Sőlőši was mostly intermediated through the aforementioned hymnbooks of Hlohovský, Cithara Sanctorum and the Hungarian version of Cantus Catholici.

Gregorian chant is traditionally one of the most important components of the Roman liturgy. Cantus Catholici includes 17 directly adopted plainchant melodies. The low number indicates that cantionals avoided this intricate genre for practical reasons. They were hardly memorable for a common human and so Sőlőši chose to include simpler plainchant such as Pange lingua gloriosi (Sing, my tongue, the glorious) or Mitit ad Virginem (He sends to the virgin), in which each syllable is mostly set to a single note. Translation of such choral texts in Slovak so that they could be synchronized with the rhythm music represents a challenge, in which Sőlőši succeeded and for which is duly credited as a poet.

In addition to Gregorian chant, the group of eldest melodies consist of Latin cantia, traditional to areas of Germany and Czechia in the 14th and 15th centuries. A great part of these tunes transitioned to Cantus Catholici through Czech and Moravian cantionals. In particular, the melody of the hymn Vesele spívajme, Boha Otce chválme (Let us sing in Exultation) was adopted from the hymnbook of Hlohovský, although the melody is documented as early as 1410. Protestant environment appropriated German and Czech tunes so well, that the Cithara Sanctorum hymnbook only included their text with a note ‘has its own tune,’ therefore in the Slovak area, they were first released as part of Cantus Catholici.

Two-thirds of tunes originate from Central European cantionals of the 16th and 17th centuries. They are stylistically different from the tunes of previously mentioned sources. They are mostly characterized by the influence of polyphony, fixation of text metre with the rhythm of its music and in the majority by their modality. The greatest number is of German roots. Thanks to numerous German populations in many Central European cities, the melodies spread quite fast in the area. In the Hungarian Kingdom, many were already popular prior to Cantus Catholici’s issue. Some tunes of German origin are Seid fröhlich und jubilieret (Be happy and rejoice) or O güttigster Herr Jesu Christ (Zavítaj k nám, ó z výsosti– Come to us from Highness). 30 tunes within this historical layer are derived from Czech sources. Czech group is stylistically more conservative, most likely due to Sőlőši’s almost exclusive orientation towards two major sources of Hlohovský and Rozenplut hymnbooks. From these, carol Poslouchejte kresťané (Hark, Christians) is notably known. Po upadku czloweka grzeszneho (After sinful man’s downfall) and the other 11 are of Polish provenance, these were mostly adopted through older Czech and Hungarian hymnbooks. Three odes from a French psalter and two Croatian songs are an interesting curiosity, Sőlőši may have discovered these during his studies in Styria or during his stay in multi-ethnic Trnava.

There are in total 18 melodies from traditions within the Hungarian Kingdom, the eldest documented being hymn Moc Boží divná (Astonishing power of God) from the year 1560. Authorship of nearly all of these melodies is either unknown or dubious, probable lyricists and composers of some might be protestant poets Juraj Tranovský (1592-1637) and Eliáš Láni (1570-1618). Tunes gathered from protestant hymnbooks form a substantial part of Cantus Catholici and remained in catholic hymnbooks to this day, e.g. melody of song Ač mne Pán Bůh ráčí trestati (Though God wills to punish me). Though sources of the remaining 36 melodies from the 1655 issue remain unclear, it is impossible to credit Sőlőši as their author, similarly to texts. Their stylistic aspects are disparate, and influence or appropriation of oral tradition is again highly likely.

Content of Cantus Catholici hymnbooks became a part of communal spiritual singing in the entire multilingual Kingdom of Hungary. Texts and melodies hitherto unknown were becoming a part of everyday practice rather slowly and many were rejected. Despite this, a greater number of hymns were widely accepted and tens of hymnbooks since the 17th century cited or adopted their texts and melodies. Catholic and protestant parishes continue singing many of the aforementioned hymns to this day and part of them also found their place in the folklore, predominantly the Christmas carols. The hymnbook thus served in transitioning intangible cultural heritage, forwarded what it borrowed. It offers an image of historical practice in notation, typesetting and means of local printing presses and it is a subject of linguistic and poetry studies.

Excerpt of St. John Chrysostom homily in the beginning of this article presents an illustration of the ideals important in the 17th century in parallel to being an example of Cultured Slovak. Baroque human, bound to meekly endure all the struggle, thinking of the reward awaiting in the afterlife; world polarised to good and evil; theological combats between Christian denominations; or more strictness in control over behaviour within communities from the side of lordship and church are problematics intimate to moving forces behind the creation of Cantus Catholici. However, undeniable facts are that together with Cithara Sanctorum, the hymnbooks laid a base for regulated Slovak church music tradition; that right in its beginnings the standard was set high; and most notably that their contents are a part of everyday life in the Slovak area for over three centuries.

Bibliography

Blažencova, Ľubica. ‘Cantus catholici – prvý tlačený katolícky spevník (Okolnosti jeho vzniku, obsahové bohatstvo a niektoré špecifiká piesní)’.

Hrušovský, Ivan. Slovenská Hudba v Profiloch a Rozboroch. Edícia hudobnej literatúry. Vol. 29. Bratislava: Štátne hudobné vydavateľstvo, 1964.

Kačic, Ladislav, Svorad Zavarský, and Peter Žeňuch. ‘Cantus Catholici (1655): The First Slovak-Latin Catholic Hymnbook’, 2013.

Lauková, Silvia. Cantus Catholici v interpretácii. Nitra: Univerzita Konštantína Filozofa v Nitre, 2010.

Ruščin, Peter. Cantus Catholici a Tradícia Duchovného Spevu na Slovensku. Bratislava: Ústav hudobnej vedy SAV, 2012.

Zagiba, František. Dejiny Slovenskej Hudby od Najstarších čias až do Reformácie. Bratislava: Slovenská Akadémia Vied a Umení, 1943.